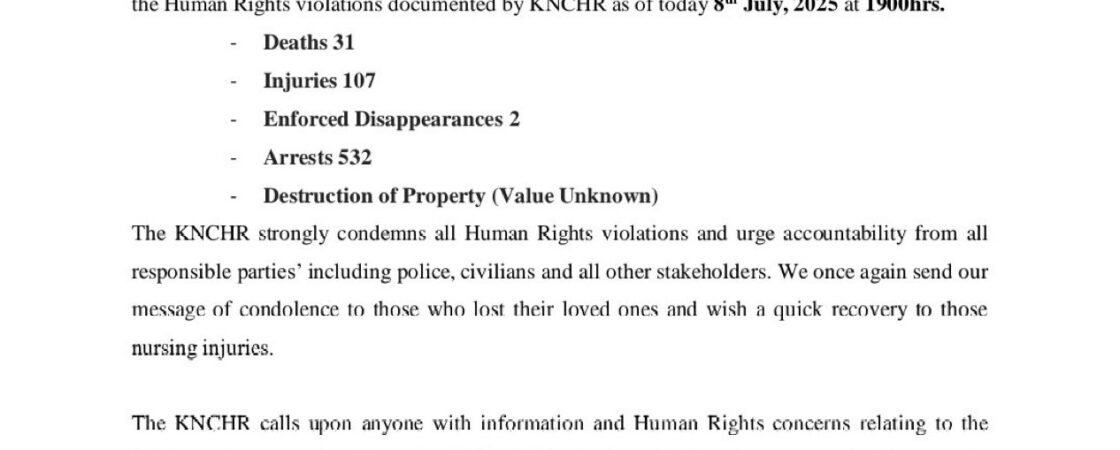

Kenya’s yearly Saba Saba Day turned deadly once more on July 7, 2025, following nationwide protests that were met with what human rights organizations are calling excessive and disproportionate police violence. In a stark contradiction that has rampaged the country in anger, Kenya National Commission on Human Rights (KNCHR) quoted 31 deaths from protests, in a blistering contradiction with the National Police Service’s reported 11 deaths.

The growing gap between state and civil society accounts conceals more than a numerical difference. It signifies a chronic issue, systemic underreporting, police impunity, and repeat cycles of violence which have for so long tainted Kenya’s electoral and political process. As the country continues to struggle to shake off widespread economic discontent, high unemployment, and calls for President William Ruto’s ouster, the Saba Saba protests this year struck a raw nerve beyond remembrance they are now a live critique of the state’s human rights record.

Saba Saba, or “Seven Seven” as the name is in Swahili, is remembered on the 7th of July 1990, when the first massive pro-democracy protest against the regime of President Daniel arap Moi took place. From a protest for multi-party democracy, it has evolved into an annual remembrance of civil rights, government accountability, and people’s defiance.

Saba Saba in 2025 is no longer mere commemoration, but an open battleground. The protests this year were fueled by growing anger against President William Ruto’s government, such as perceived mismanagement of the economy, unpopularity of tax increases, and corruption charges. The protests, spearheaded by youth and civil society activists, called for Ruto to step down, citing a worsening cost of living and what they call degradation of democratic institutions.

It was in a KNCHR press release released on July 8 that the commission counted 31 deaths, dozens of injuries, and extensive police brutality and property destruction. The statement was of the majority of the cases occurring in Nairobi, Kisumu, Eldoret, and Mombasa all hubs of previous political violence.

Kenya Police gave a conflicting report, however, reporting only 11 deaths and attributing the initiation of violence to “criminal elements” among the protest movement. The policemen were also accused by the police of being “within the law” and resorting to “self-defense.”

This glaring omission is a cause for concern as far as transparency and independent monitoring are concerned. In a 2022 report, the International Justice Mission (IJM) documented 42 convictions of police officers for abuse of office between 2017 and 2022, but how rare but possible it is to prosecute officers in Kenya. The report also alluded to systemic problems late investigations, intimidating witnesses, and poor forensic practices that too often exclude justice from being delivered.

What makes the KNCHR report especially concerning is that it follows historical trends. From the 2007–2008 post-election violence to the 2022 protests over disputed presidential election results, police reactions in Kenya have been criticized on numerous occasions for deploying live bullets, arbitrary detentions, and brutal force.

Al Jazeera coverage of the July 7 events included chilling shots of police in uniform shooting at fleeing protesters, tugging civilians into blacked-out vehicles, and beating up demonstrators. Several dozen witnesses told the network that they had done nothing wrong but were attacked merely for having participated.

This is not just a breakdown of law enforcement for human rights campaigners it is a crisis of governance.

“We cannot afford to have another generation of Kenyans get killed for asserting accountability,” a KNCHR spokesperson said in their press briefing. “This is the worst of our history coming back at us.”

The KNCHR has been at the center of Kenyan human rights activism since its inception in 1992, often having to operate in difficult political climates. This year alone, the commission urged citizens to report abuses, injuries, and deaths on hotline numbers and secure online platforms. As much as this method assures people’s participation and on time collection of data, it is also sources of contention regarding data credibility in the absence of total forensic analysis or standalone monitoring crews.

Where access to media and NGOs is lacking, deaths can go unreported or misclassified, and where there is tension, police can slow down or even block investigations altogether. This complicates KNCHR’s job and underscores the essential need for open, well-funded, and unbiased investigations of protest-related violence.

What happened at Saba Saba 2025 is no mere one-day tragedy it is a reflection of an increasingly polarized, disillusioned society. Kenya’s youth, so many unemployed or underemployed, feels itself outside of power. The state’s recourse to riot police, tear gas, and curfews only serves to increase alienation.

Human rights organizations, civil society, and even Parliamentarians are calling for an independent commission of inquiry into Saba Saba violence. They argue failure to do so would mean more protests, more casualties, and a possible recurrence of past political crises.

Kenya stands once again at the crossroads of democracy. The tension between reports from the state and independent journalism read the various casualty figures is something that needs to be addressed with urgency. While the KNCHR investigations continue and the country waits for justice, this one fact remains certain, a democracy that silences its people with bullets is no democracy at all.

If Saba Saba must be a symbol of hope and not terror, then the government must choose accountability over impunity. Counting the bodies alone is insufficient; Kenya must count the cost of its silence.

Saba Saba 2025: KNCHR Reports 31 Deaths, Exposing Alarming Gap with Police Claims Amid Brutality Allegations