Kenya’s 2011 Somalia intervention, initially marketed as a heroic operation against Al-Shabaab, has left behind a complicated inheritance of proxy war, sovereignty issues and enduring instability. Think tank analyses and peer reviewed works of the period hold that Kenya’s deployment of clan aligned militias later rebranded as Jubaland troops represented a risk that continues to shape security realities in the Horn of Africa.

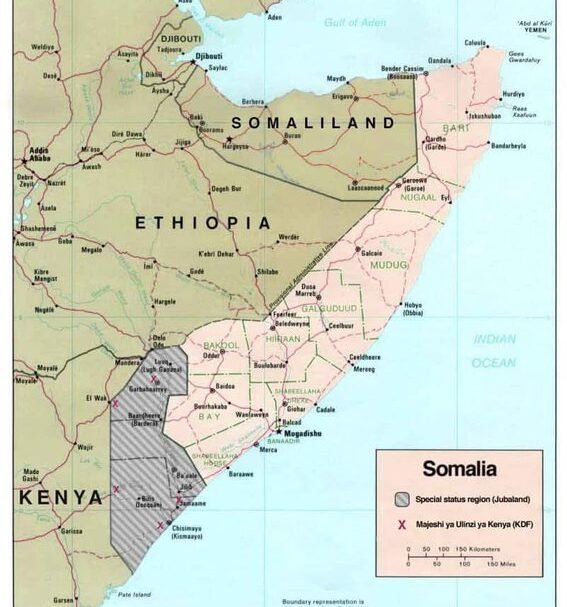

In October 2011, Kenya launched Operation Linda Nchi, a huge military incursion into southern Somalia aimed at destabilizing Al-Shabaab after a series of kidnappings and cross border attacks. While Kenyan soldiers led the charge, Nairobi also spent money on a twin policy, training Somali proxy militias.

A report by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) shows that Kenya had been training Azania militias, who were later integrated into forces of Jubaland. The militia groups, led by Mohamed Abdi Mohamed former Somalia Defense Minister were predominantly made up of the Ogaden clan. Training reportedly took place in Isiolo, far into Kenya.

American and British envoys at the time cautioned against a unilateral move, and asked Nairobi to go through the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM). Kenya proceeded nonetheless, driven by the dream of creating a friendly buffer zone in Jubaland, which would safeguard its northeastern counties from Al-Shabaab attacks.

The Jubaland project represented Kenya’s profound military involvement in Somali politics. On the surface, it provided Nairobi with an indigenous partner force with local legitimacy in a bid to secure southern Somalia. In reality, though, it placed Kenya squarely in the midst of Somalia’s unstable clan politics.

The Ogaden militia fighters fought alongside Kenyan Defence Forces (KDF) in operations against Al-Shabaab, which augmented the KDF’s presence but this close link too blurred Somalia’s vulnerable sovereignty and Kenya’s security imperatives.

By backing a particular clan aligned unit, Kenya inadvertently exacerbated clan rivalries. Jubaland turned into a counterinsurgency tool and an incitement factor in Somalia’s divided political landscape frequently running counter to Mogadishu’s attempts to project central control.

The strategic risks of such a policy are well documented. In a 2016 report in the Journal of Eastern African Studies, it was argued that reliance on proxy militias is bound to result in instability when militias are under stress or demobilized. The report outlined the way defeated Jubaland forces retreated back into Kenya, bringing insecurity in with them and not exporting it.

This trend is marked by the underlying issue of proxy warfare: militias are capable of providing short-term tactical victories but are not as likely to produce long-term stability. If left behind or overwhelmed, they can reorganize as spoilers, destabilize borderlands or propel criminal economies.

For Kenya, this meant the Jubaland experiment had the potential to turn its buffer strategy into a boomerang effect, subverting the very security it aimed to create.

Aside from the war costs, Kenya’s policy of proxy also created sensitive issues of sovereignty. By turning Jubaland into a semi autonomous state with loyal militias, Nairobi appeared to undermine Mogadishu’s central power. Somali leaders often accused Kenya of meddling in internal affairs and Kenya rationalized its actions as being in the interest of securing its borders

The tension had strained diplomatic relations between the two neighbors, especially during conflict periods for maritime boundaries and trade. Essentially, Kenya’s approach to immunization against instability heightened political engagement in Somalia, making withdrawal or disengagement an increasingly difficult task.

Kenya’s militia experiment has to be put into perspective. Across Africa and globally, governments faced with insurgencies have increasingly turned to proxy forces as a fiscal measure. Ethiopia’s use of regional militias, Uganda’s use of allied forces in the Democratic Republic of Congo and American reliance on local allies in counterterrorism efforts all point to this broader trend.

But the Kenyan experience serves a basic warning: political settlement is required for proxy war, lest war be perpetual. Deployment of clan troops reinforced divisions rather than bridging them. Despite Al-Shabaab remaining a credible threat fragmentation of power in Jubaland complicates stable governance in southern Somalia.

As the African Union Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS) winds down and Somali forces increasingly take up security roles, Kenya stands at a strategic juncture. Should it maintain support for proxy militias in Jubaland or shift towards aligning with a more consolidated Somali state?

The Azania militias’ record and the Jubaland experiment are a sign that unilaterally motivated mechanisms have high cost labels. Proxy fighters may achieve short-term bargaining power but they may end up passing on instability, undermining sovereignty and capitalizing on new cycles of violence.

For Somalia, the combination of foreign supported militias makes fragile state building even more challenging. For Kenya, it reminds us of the danger of a speedy solution to the long term security issues. And for the region as a whole, it serves as a reminder that stable peace will not be attained through military solutions but political ones founded upon legitimacy and inclusivity.

Kenya’s 2011 decision to train Somali militias marked the turning point of its security policy. It began as a calculated means to address Al-Shabaab but became a complicated blend of military entanglements, clan politics and sovereignty issues. The Jubaland experiment is evidence of the pitfalls of proxy warfare, while it gives immediate battlefield victories it has a tendency to destabilize the very areas being secured.

While the Horn of Africa grapples with shifting loyalties and the gradual pullout of foreign forces, Kenya’s shadow war lessons are harsh. Proxy militias are no substitute for political settlements and short of healing the roots of conflict, they may do more harm than good.

When Proxies Fail: How Defeated Jubaland Militias Fled Back to Kenya